It’s been a little over 25 years since the first digital film was released. The first fully digital Live Action Feature Film (allegedly) ever made was made by Neil Johnson, A British Director, who has gone on to make 15+ feature films and a couple dozen TV shows and in definitely a fan of his work including his most recent film Rogue Warrior: Robot Fighter starring Tracey Birdsall.

Many times I’ve sat down with Neil and we have spoken about a wide range of subjects, but this time I virtually sat down with Neil Johnson and fired a few questions about the his film The Demons In My Head and its making. Here you go! Enjoy!

What inspired you to make possibly the first ever all digital feature film?

I actually don’t know if I was the first. I could say for sure that it was the first feature film shot anamorphic digital, edited completely online on a computer system, mastered and sound mixed on a computer system, and even projected digitally in the cinema. This was 1995-1996. I say I could be the first, but who knows. I can say the film was finished digitally with VFX, released in the cinema for a limited theatrical, which was expanded to a few other cinemas later on 35mm film, and sold to 22 countries around the world on VHS, and later DVD.

Can you explain what you mean by digital, and why was it a big deal back then?

Let me backtrack a bit. My career up until then, had been directing music videos, documentaries and TV commercials. Before digital there was film and crappy video tape. At film school I shot film and 3/4 inch videotape. If you were ever serious, then you shot 16mm or 35mm film. If your budget was low, it was videotape. I was British and shipped to Australia at a young age. I had a strong British accent, a bit of a lisp, and I was small, so I was bullied on an almost daily basis. Australian people in the 70s were often racist and bullies, at least the young people were where I lived, so I was constantly getting beat up and called racist names.

Racist names? Fired at you, you mean?

Classic Australian name calling like “Pommie Poofter”, which means “Gay British Person”. I was always the last to be chosen for the sports team, I was a Sci-Fi nerd and even the girls targeted me, because I was not speaking with the “manly” Australian slur. I was too polite or “nice”, so I was told. I eventually learned to fight and clobbered people in the face before running away, all nervous that I may have knocked someone unconscious, or worse. I was friendless for many years, and I wanted was a friend. Later in high school I was friends with all the other immigrants in the school, who may also have been bullied. But I was the only British person I knew, so I still felt alone.

So fast forward to film school… There was a point where the lecturers were telling me how things were done, how films were made, etc. Everyone formed groups to make films. All except for me. I was the odd man out. I wanted to make Science Fiction and Horror films. I was heavily discouraged from this, so I went it alone during film school. I graduated, and received my qualification, but never really clicked with the film scene at that time, so I worked in television, and dreamt of adventures in cinema.

Later on I went to try and get funding for a film from the Queensland government’s film board, and they said no, because Science Fiction wasn’t their agenda. So I shot video-tape, and found ways to make it look like film. Soon after, I got a flood of music video work, because I was the guy who could make something like like 35mm for a “video” budget.

Lets shift back to the film.

There was a format called Digital Betacam, and this was not just digital. With the right lens you could shoot anamorphic, to give you a true widescreen 35mm look. This was unheard of. It was digital videotape (from memory it was 2:1 compression) Most people didn’t use this, but I was excited. I remember working for one of the big production houses in Brisbane, Australia and we made a TV commercial on Anamorphic Digital Betacam, and blew this up to 35mm film. It looked ok, but was very electronic-looking. At this time, I was using computers for off-line editing, but then mastering on glorious video tape, because the computers could not handle 25 frames per second.

Soon after this, I worked for a new company that had purchased the first ever online computer editing system. It was called the Imix Turbo Cube. It cost around $134,000. It could edit up to 1 hour of mastered video footage. The quality wasn’t great, but I set about making a short Science Fiction film, called “The Plague”, in 1995. It was ALL digital, and it even had electronic VFX matte paintings. And it looked like film, sort of (I had some tricks). The developers of the editing system in the U.S. came to visit and didn’t believe what I did was actually possible. They sat with me all afternoon questioning how I had done matte paintings, etc, and then asked me for a list of what I would do to improve the system. Soon after this they developed a better quality system with 3 hours of online storage at 3:1 compression, and it could handle anamorphic. It was called the Imix Stratosphere. Parts of this later became Final Cut Pro Version 1. I dared dream, and suddenly I had all the tools in front of me to make a fully digital feature film, edited and mastered in a computer.

Did you feel like you were breaking new ground at the time?

It sounds glorious, but at the time, I felt like a bit of a chump. I wanted make a film on widescreen 35mm, but had no money for this. The cheapest you could make a feature film for on 35mm would be $130,000, but traditionally it was more like a $1,000,000. So I made a feature film with what I had. I was 28 years old, and had been a director since the age of 21, but I looked like a kid still, and even finding an Australia crew or actors to work with me was nearly impossible. The people in the film industry back then were basically bullies who would talk down to you because you weren’t doing things the “proper” way. There was a thing in the culture called “The Tall Poppy Syndrome” where anyone who dares to be great is cut down to size but all those around him. I once begged an established Director of Photography to train me, when I was 18, and he refused because he one day I would take his job. I knew it was going to be difficult.

I found $15,000 rented the cameras and started shooting a strange sci-fi horror film in my own house. Some of the crew I had were nice, and some were daily telling me I was doing it all wrong. It was quite horrible at the time.

What was the basic storyline of The Demons In My Head?

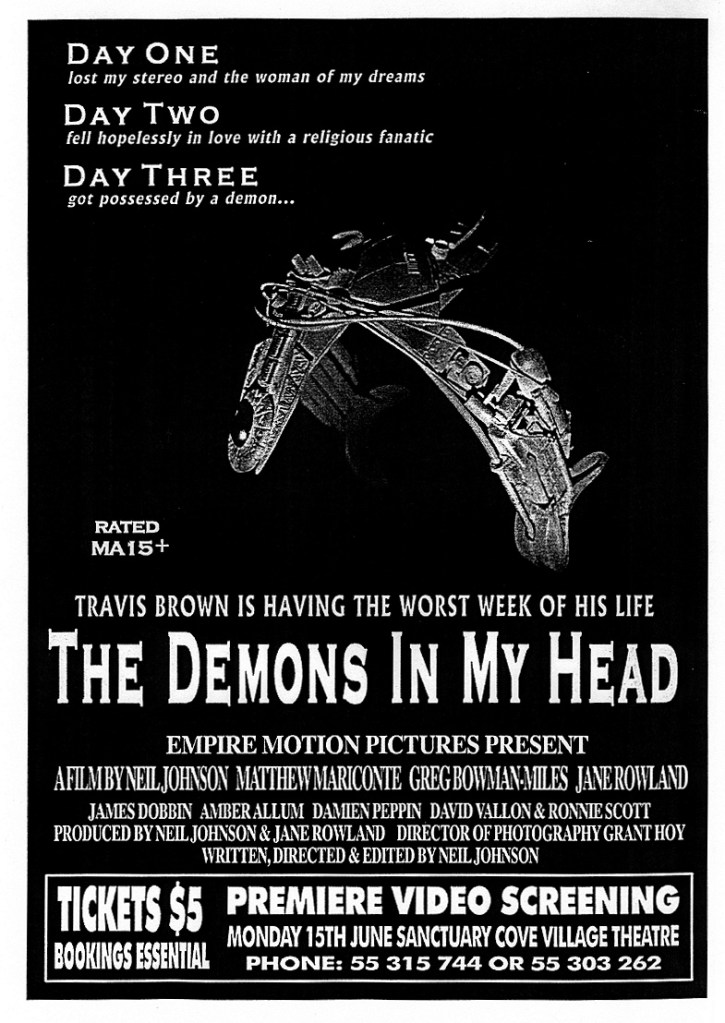

Here’s the pitch for The Demons In My Head: Travis Brown, a 25 year old underdog-type guy lives with 2 other people. His gay best friend who is secretly in love with him, and Larissa, a girl whom he is in love with, but she has no interest in Travis whatsoever. A circular love triangle. So, in the space of 48 hours, he loses his job, a meteor crashes in his backyard, and the love of his life hooks up with Travis’ arch nemesis from high school. Annoyed and depressed, Travis breaks open the meteor to find a strange headset inside. When he puts it on, it slowly starts to transform him into a more manly sinister version of himself. Essentially he gets possessed by a demon. I had to tone down the Sci-Fi elements because NO ONE wanted science fiction films in 1995-1996, or so I was told. Originally it was going to be called “There’s a Flying Saucer in My Backyard” or something like this. I couldn’t afford a flying saucer.

I’m starting to detect the film’s theme was reflecting your own life a bit there.

Maybe a little, but it really wasn’t me at all. I was very distant from the character in the film. Many people said, or assumed Neil Johnson was Travis Brown, but that was people who didn’t know me.

How hard was it making a feature film in Australia in 1996?

I know the neighbors hated what I was doing. This was the Gold Coast region, and nobody there made independent movies. I warned everyone in the street, that there would be extra cars parked, cameras, demons running around, and maybe screams sometimes. They called the police on me quite a number of times. I remember one neighbor every day would mow his lawn (which didn’t need mowing), so I would politely ask him to stop. In the end, every day I would bribe him $20 to NOT mow his lawn. (this was a lot of money back then). The Director of Photography was used to working on big TV and film productions. He was eager to shoot on a new camera system, but he rapidly became VERY annoyed at me and the lack of equipment. I had a certain look in mind, but as he was used to a BIG crew, bright scenes and crisp 35mm film, he didn’t want darkness and spookiness. We clashed a bit, but I remained mostly polite. It did traumatize me, so I shot my second film myself and was WAY happier with the results. He really did a good job shooting the film in retrospect, which is why it still looks good, but we didn’t agree on lighting choices, etc.

The hard day (and here is the lesson) was the day I decided to do a cameo as the Arch Demon. We had some pretty amazing make-up people who were just starting out. (They went on to work on the Orcs on Lord Of The Rings which looked VERY similar) So I used hair removal cream to remove all the hair on my body and then they glued latex directly to my skin. I was completely naked (save for a modesty garment which had to be removed during the makeup process- thankfully no one sniggered). The make-up took 6 hours, I had vampire teeth, fake nails, contact lenses, blood and the works glued all over me. The only thing I didn’t like was that that they put hair spray in my hair. I looked like an 80’s demon-hair-metal rocker. So then I had to direct myself, and the film for that day IN make-up. Latex is VERY sticky, so I couldn’t really sit down or touch anything without becoming glued to it. I enjoyed being a demon, but will NEVER again try and direct myself. It’s a nightmare. For a full 3 months after this, I developed a terrible skin rash that eventually healed.

For the gore scenes we used real intestinal meat. There was this wonderful actor Ronnie Scott, who was a vegetarian. He played one of the strange demons and he ate raw flesh (by his own choice) on camera…. I didn’t ask him to but I liked it. He went almost overboard with the performance, scared most of the crew by not being able to drop his flesh eating demon persona, and then proceeded to throw up most of the evening. Following these scenes, the caterer served up sausages, and no one ate anything. I was told later that the role sent Ronnie a bit crazy and he disappeared into the outback of Australia, never to be heard of again. Another great actor, David Vallon was already an established star of stage and screen in Australia. He was a delight, but his did start a few arguments on set with some of the other associate producers. I had to officially side with him, because I couldn’t lose him as an actor, but I could anger a producer or 2. It’s the curse of film-making. For a time, the actor is king on set, wielding all the power, until you have the film in the can. I worked with David Vallon again for my second film.

The main producer of the film was Jane Rowland, who acted in the film (she played Marcia, a religious door-to-door type who eventually gets possessed by a demon herself) It was probably hard on her wearing many hats, but she carried it well. We did clash on set a few times. She was great on the day when I was a demon. It was a 20 hour day, and was surprisingly un-stressful, despite the long hours. I think everyone was in awe of the make-up effects.

Did the film get a big release?

So the film was finished on budget, on-time, and then fully edited on a computer. It played in the cinema in Queensland Australia to some small acclaim. One screening, I recall, the gore was too much for a young man and he actually fainted. I helped carry him out of the theatre.

Jane was then essential in getting the film into the film markets in the United States and in Europe (Cannes). We sold 22 territories through a U.S. company called Raven Pictures (from memory) who collected a couple of thousand dollars in sales and then quickly went “broke”, taking all the money with them. But Jane did well, getting the film sold at least. Plus we got coverage in The Hollywood Reporter and much of the International press. We even got a nice write up in Fangoria Magazine. One reviewer described the film as Doctor Who on acid, which is accurate.

When it came to blowing the $15,000 movie up onto 35mm film, the cost was $35,000, double what the film actually cost to make. When I stated telling people what I had done (Film commissions and even the film press) I was universally panned and ignored. Everyone in Australia told me I was a fool to have done this on digital. They were scathing and nasty in their comments. I was called an amateur, an idiot, and told I could never get any government funding from the film commission, unless I stopped doing horror and Sc-fi, and focussed on “drama”. One person high up in the industry told me directly that I didn’t have what it takes to be in the film or television industry, that I should find a career elsewhere.

The film was released in places like the UK, Germany and the USA. I could never get the film released in Australia. We made the top ten video in the VHS video rentals in the UK. The regular people who saw the film in Australia were proud, even the neighbors who had been annoyed, were suddenly proud and excited by this, but the Australian film industry whole-heartedly rejected my career. I made 1 more film there and then promptly left the country. One person in Film Queensland (the government film commission) told me that I was too commercial and successful, and that I should go to another country. Again, saying they would never fund or support me. They were completely right to say that.

You seem to not so much impressed with Australia very much listening to some of your answers

Look, I do speak very negatively about Australian people here and there. Often they are bullies, and they are not always ahead of the game, but this is the culture, which in other respects make they love-able. They are not bad people, but the cultural bias pushed me to greater heights, so I am strangely thankful. There are some amazing people there, and all the actors in the film, I can honestly say, were the true champions in this story. They made the film what it was, and made the journey worthwhile. They gave as much as I gave on set.

So what changed after this? Where did this lead you?

Fast forward to 1999. The “World’s First Live Action Digital Feature Film” (with caveats) had been finished 3 years ago in 1996, Released in early 1997 to NO acclaim, and I was planning my second and third feature film. I attended the Screen Producers’ Association of Australia; an event in Sydney where all the top producers and directors got together. It was odd. I saw George Miller standing in a corner watching everyone. This was the guy who made Mad Max and The Road Warrior. Long tousled hair, and actually a friendly demeanor. I probably looked lost, and he looked across at a fellow long-haired person and he smiled warmly. It was one of the few acts of kindness I had encountered in a long time. It was all it took to make me feel welcome amongst my “peers”.

I started telling some of the big Australian producers I had made an all digital feature film. They told me (again) I was wrong to do this, and that I should have shot 35mm film. A lot of finger waving and lecturing! Jane Rowland, my hardy co-producer really worked the 3 day event. She was bold and very business-like (compared to me, the 28 year old film maker who looked like he was 18).

It turns out that George Lucas and Rick McCallum were there. George had just finished Episode 1, shot on film, and was looking to shoot Episodes 2 and 3 in Australia. Jane Rowland got into Rick McCallum’s ear and told him how we had made a full digital film 3 years ago. The ears pricked up. George was planning to make Attack of the Clones all digital, so they wanted to talk. I explained my process: I shot Anamorphic Digital Betacam on a Sony camera, edited entirely in a computer (in anamorphic 16:9) in 25 frames per second.

To make it look like film: Video footage has a thing called interlacing. The “video look” that every one hates. Each video frame is made up of 2 fields, an upper field and a lower field. It is this field switching that gives the video sharpness. I removed the lower field in the edit room and doubled the upper field. It removed some of the video look immediately. Then I shot some 35mm film on a black screen. I took the this film footage and layer over the grain onto the video image. It looked a LOT like film. I also used a lot of ND grad filters on exterior scenes to help the Dynamic Range of the image- again imitating film.

Rick McCallum told me that they had shot a scene in Episode One (Anakin’s bedroom) on a new Sony Prototype Digital HD camera as a test. They weren’t happy because it had the “video look”. Perhaps my advice for shooting digital helped, perhaps not.

I briefly met George, who was VERY unassuming. He reminded me of myself. Not fully comfortable in the room and also distant. There was a lot of ego in the room, but he and Rick were just hungry for information, and insulated from all the chatter. We exchanged email addresses and left it there. A few weeks later I mailed off VHS tapes of my little film so that they could see the results of what we discussed.

Did they watch it? Who can say… perhaps he saw the first 5 minutes and turned it off…. George was busy writing Attack of The Clones at the time. Cut to 2004, there was a deleted scene from Attack of the Clones, that had an identical scene set-up to the opening of The Demons In My Head, even 2 lines of dialogue were also the same… was this a sub-conscious homage to the world’s first digital feature film? Who can say. If it was, it was a great compliment.

Am I proud of The Demons In My Head? At the time, yes. In later years, not so much. It was an ok first feature film, but not anything close to being good. But in the last 2 or 3 years, I realized this was 25 years ago and worth discussing again. The film lives on and still occasionally gets re-released world wide. As a matter of history, it’s a worthy achievement, because sometimes being the smallest kid on the block can take you to heights you never imagined. I don’t believe I had anything with kickstarting the Digital film-making experience. this was more in George Lucas’ hands than anything else, but I did help breathe life into something new, and at the time, I never knew where the journey would lead.

How can we see “The Demons In My Head”?

Some of my later films are being re-released on streaming. Following the first edition of the film, I did a special edition in 2000 with MORE vfx, then I re-cut the film shot extra scenes, and renamed it Nephilim, to fight all the bootlegged versions out there. So technically there are 3 versions of the film.

I am considering making a new 4K version of the film in its original cut. I am expecting to have this released soon, so I can put it to bed. The original cut holds up nicely for what it is, and I think it should be remembered in its original form. I expect in the next 3-6 months it will appear again. There are VHS tapes and old DVDs available, but these are becoming rare. Any version you see released anywhere is released WITHOUT my permission (or payment), and I never got a cent for the film. The film was re-named the film “Demon Nightmare” in Germany to “hide” the release. I have been throwing lawsuits around here and there to get the film blocked from unauthorized releases like. Another company re-released it again in 2018 in Germany with strange cover art. For a movie that is apparently not the best, it still makes money, so it has some value. It used to annoy me, now I realize that people (distributers included) will steal your film no matter what. You can sue them all, but in the end you lose time and you get your legal expenses back, and that’s about it.